What is Incremental Computation?

Incremental computation (abbreviated throughout as IC) is a software feature that takes an input and attempts to do the minimum necessary “work” to update the outputs. This is in contrast to approaches where outputs cannot “update” and must be recomputed as a full refresh. [wikipedia]

For Example: Here is an incremental and non-incremental approach for implementing an “unread messages” count in a chat app…

| Full Refresh | A count() query: SELECT COUNT(*) FROM messages WHERE is_read = false; |

| Incremental | Use logic (code or SQL triggers) that increments and decrements an unread_messages counter. |

IC tends to be implemented in one of two ways: (1) Ad-hoc, in code, as a way of incrementalizing one specific computation, or (2) As a system, behind an API.

Incremental Computation System

An IC System is a framework that handles the complexity of incremental computation, while allowing the user to interact with it simply.

For Example: The Rust language uses an incremental computation system in its compiler. Changing a single line of a file in a large code project results in fast compilation time by only recompiling the parts affected by your change. Users do not have to indicate which files changed, or what is affected by those changes, it happens automatically.

From the description above, incremental computation feels intuitive. Incremental aligns with how things work in the physical world: Stores aren’t constantly recounting their inventory, they’re just tracking what comes in and what goes out. But the reality is that much of the computing world still follows the full refresh model.

important

If incremental computation systems are more efficient and align with the real world, why aren’t they the default?

- Developers find it difficult to “think” incrementally, and prefer to specify computation in terms of absolute inputs, even if this results in higher costs/longer compute times.

- It’s tricky to wrap a generalized IC System in an API that hides the complexity without also limiting the utility.

In spite of these challenges, incremental systems have already succeeded in a few areas:

Compilers: As mentioned earlier, some compiled languages like Rust. and Java allow for incremental compilation as a way of speeding up build times, this is done via a system that can track and only recompile the code affected by a change.

DOM Updating: At it’s core, React provides a framework for changing state in a set of data and having the DOM (the browser) incrementally update only the minimum necessary parts of the UI.

Formatting and Linting: It may be surprising to hear that many IDE’s still use a full refresh approach to recompute syntax highlighting and re-lint an entire file on every keystroke. Even with today’s powerful processors that introduces latency, especially on longer documents. (Have you noticed that your IDE won’t even try to highlight longer documents?)

The VS Code team at Microsoft recently ported a non-incremental syntax highlighting extension to use incremental algorithms and drove a 10000x speed-up. Parts of GitHub use a system of IC called tree-sitter.

Deno, the runtime for JavaScript and TypeScript that is in some ways a successor to Node.JS, implements incremental algorithms in it’s formatting and linting features too.

Why no popular IC system for Databases?

When applied to databases, the concept of an incremental compute system is referred to as Incremental View Maintenance (IVM). A view is a saved query, and the role of an IC system is to incrementally maintain it, turning it into a materialized view.

But as of 2022, IVM is still not widely implemented or used. Postgres contributors have been working on IVM since 2013, Oracle and, more recently, Redshift have some incremental capabilities, but limitations prevent them from being useful in most scenarios.

Databases do so much repetitive data fetching and transformation work. They are the first place you’d expect to find IC systems, why don’t they exist?

The simple answer: They weren’t built that way.

Databases have a hammer: one-shot SQL queries, and the paradigms required for incremental view maintenance are completely different.

Why Databases need Incremental Compute

For those building web and native applications, the introduction of good IC Systems enables two shifts discussed in detail below: “Code-centric to Data-centric” and “Read-centric to Write-centric”. These shifts remove complexity, increase capabilities, and generally align better with modern application architectures.

Code-Centric to Data-Centric

In a code-centric architecture, the database is more accurately a data store and most of the logic and transformation (and incremental work) happens in code.

In code-centric apps, lots of application code could be described as homemade incremental computation. Concepts like callbacks or hooks in server-side frameworks are often used to this effect.

There is a lot of discourse about how “homemade IC” in application code can easily get out of hand: it is a common source of bugs and complexity, and sometimes creates more maintenance burden than value.

Take the “unread messages” example we used earlier:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM messages WHERE recipient_user_id=123 AND is_read = false;That works fine up to a certain scale. But, at some point it will become a bottleneck, so let’s write some homemade IC:

First we’ll add a column to our users_table: unread_messages. Then we’ll add logic to increase the count every time a user receives a message, and decrease the count every time a user first reads a message.

But what happens if the sender deletes a message? Let’s add some more logic. What about if the sender deactivates their account? The logic to maintain unread_messages ends up peppered throughout application code, and future developers making seemingly unrelated changes have to stop and think: “could this impact unread_messages count?”

Even worse, what if just for a day we introduce a bug in all this new logic that messes up the count? Now everyone’s count is permanently off until we run a batch job to recalculate it.

note

This exact off-by-one error on unread messages was a bug that was pervasive in early LinkedIn.

The purpose of an IC System at the data layer is to give you a way to say “keep track of this transformation” without having to repeatedly recalculate the entire thing from the database, and without having to track and write custom logic for all the different places that may cause the output to change.

An IC System moves the logic closer to the data, where it’s easier to track and control:

“Show me your flowchart and conceal your tables, and I shall continue to be mystified. Show me your tables, and I won’t usually need your flowchart; it’ll be obvious.” - Fred Brooks, The Mythical Man Month (1975)

It’s also worth noting that broader trends (for example, React web application architectures) align well with a move towards data-centric architectures where the back-end is primarily an API on a database.

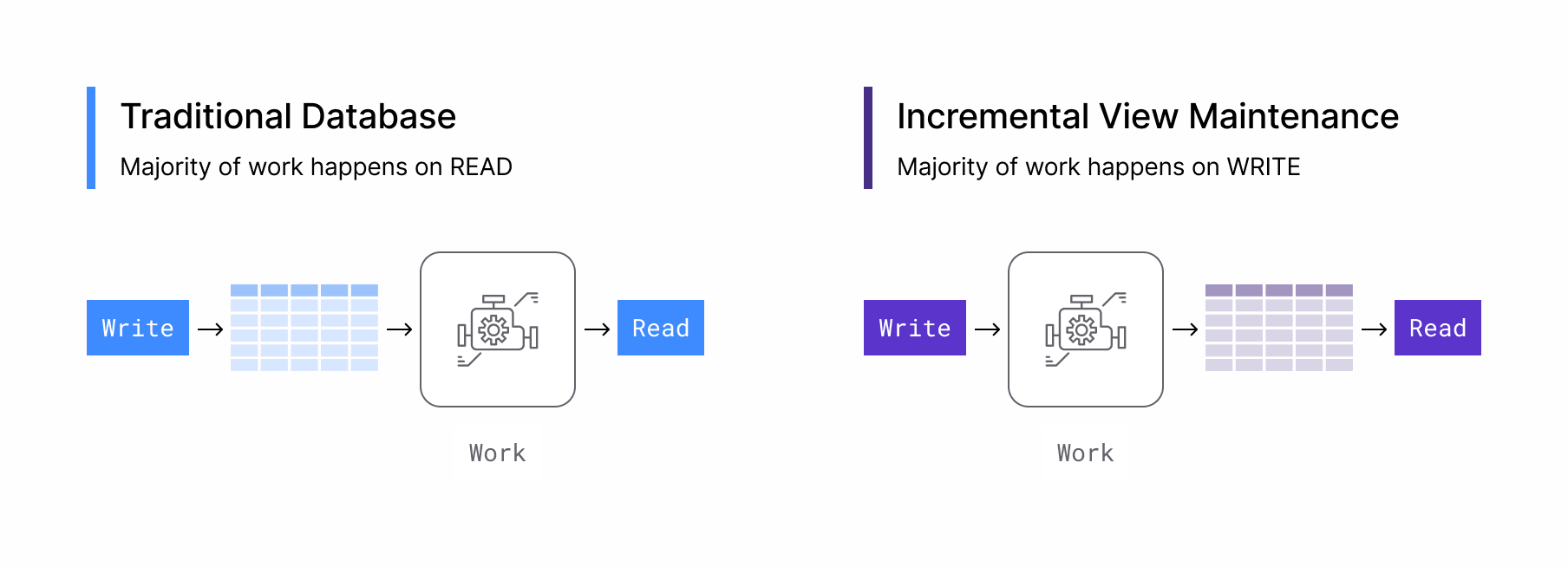

Read-Centric to Write-Centric

What uses more CPU cycles per request in your CRUD application, the Creates and Updates or the Reads? Until you start caching, it’s usually the reads. This makes no sense considering reads often occur at 10-1000x the frequency of creates and updates.

Twitter is well-known for using a write-centric architecture where all the work happens on “send-tweet” and reads are just hitting Redis caches. But most developers outside of Twitter don’t build write-centric applications, clear evidence that it’s currently too complicated.

A database with incremental computation makes write-centric architectures more accessible and even elegant by just moving the work to the WRITES in the database.

Push Capabilities

Twitter also chose to build write-centric because PUSH notifications were so essential to their product. Reactive push events from the server are a free side-effect of IC systems. For example, Materialize has a feature called SUBSCRIBE that lets clients subscribe to a stream of updates from the database. This creates exciting new capabilities for building engaging real-time applications that scale.

What does a Database with an IC System look like?

Materialize! To understand Materialize, start with a cloud data warehouse like Snowflake or BigQuery: Materialize has the same cloud-native architecture, the same separation of storage and compute, and the same SQL interface.

If you think about how you’d build a database that does the work on the writes, you first need a stream of every write. Materialize gets that either via a PostgreSQL replication slot, where it can read from the write-ahead log (WAL) or, for other databases, Materialize consumes a stream of change data capture (CDC) events from Kafka.

Once Materialize has access to a raw feed of change events, it can take what would normally be a one-shot query on a traditional database and use it to create a materialized view that incrementally maintains the results as each new write appears.

Let’s go back to that unread messages counter example, in Materialize, you’d write:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW unread_messages AS

SELECT recipient.id as user_id, COUNT(*) as ct

FROM users AS recipient

JOIN messages ON recipient.id = messages.recipient_id

WHERE messages.is_read = false;Upon receiving a CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW command, Materialize parses the SQL into a dataflow behind the scenes and processes every write through it, maintaining the unread_messages count for each user in memory.

Materialize presents as PostgreSQL, meaning you can query the view using SQL: SELECT ct FROM unread_messages WHERE user_id=123; but since it’s holding the results in memory, the response is very fast, and thousands of read queries per second are handled with ease!

Let’s take it one step further, earlier we pointed out the issue where an ad-hoc incrementally maintained count would break if the sender deactivated their account, here’s how you’d handle that in a materialized view:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW unread_messages AS

SELECT recipient.id, COUNT(*) as unread_messages

FROM users recipient

JOIN messages ON recipient.id = messages.recipient_id

JOIN users sender ON sender.id = messages.sender_id

WHERE messages.is_read = false AND sender.is_active = true;We’ve pulled in the sender info and are filtering out senders with inactive accounts. You no longer need to hunt for all the places in your code where the count might change, you can just define it in your data model.

Closing

Instead of starting with the database and trying to patch in an IC System, Materialize started with a dataflow system called Timely Dataflow and put a SQL Parser and PostgreSQL API on top. (Timely Dataflow began years ago as a Microsoft Research project co-led by our chief scientist and cofounder Frank McSherry.) This takes an extraordinary amount of engineering effort, but it gives us a more capable system. Building an incremental view maintenance engine starting with a dataflow framework was a deliberate decision aimed at ensuring Materialize can efficiently maintain queries across a complete and standard SQL syntax. As a result, we hope to power not only the next generation of data-centric applications, but new types of architecture that we can’t even predict today.

If you’re interested in building with Materialize, register for a free-trial account here, and take a read through our docs here.